A Blessed and Holy Christmas Season

The Twelve Days of Christmas

Today Christ is born in Bethlehem of the Virgin.

Today the Beginningless doth begin, and the Word becometh incarnate.

The powers of heaven rejoice, and earth is glad with mankind.

The Magi do offer presents, and the shepherds with wonder declaim.

As for us, we shout ceaselessly, crying,

Glory to God in the highest,

and on earth peace,

good-will towards men.

(John of Damascus)

Atheist Perspective on a Christ-less Season

Happy Jack wishes one and all here a peaceful and Holy Christmas - and thanks you all for visiting and commenting.

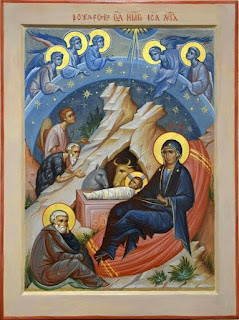

How wonderfully inclusive! Merry Christmas, Jack! Thanks for including that beautiful icon. ❤️

ReplyDeleteINCLUSIVE!!! 🤯

DeleteHow dare you! It's offered in an ecumenical spirit .. 😎 😇

Ecumenical atheists? 😁

DeleteHappy Christmas everybody!

Delete(The last 3 links all appear to be Calvinism! Even the atheists: "Calvinism is a liberating celebration of God’s sovereignty and a necessary prioritizing of God’s glory over all things." Too much to say, but as it's Christmas, I won't.)

@ Lain

DeleteAs 'Martin' would say: "Nobody is an atheist." 😇

One of his few comments Jack cautiously agreed with, minus his Calvinist/Puritan "misunderstanding".

@Jack

DeleteAnd nobody was a Christian either...

If belief is necessary to be saved, and God has created (most) people for damnation for his own good pleasure, then it's logically incoherent to say there are no atheists. Actually, if that's true, it's logically incoherent to say that anybody 'believes' or doesn't in any real sense, but anyway.

Happy Christmas Jack and all exiles from Cranmer !

ReplyDeleteMerry Christmas anonymous and all of Cranmer's erstwhile congregation. Especially Martin.

Delete@ Punster Chef

DeleteWot about Carl ... and Martin M?

And them, of course.

DeleteCranmer's Christmas musings for 2022 can be read here:

https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/in-praise-of-the-church-of-england/

Chef, now that Cranmer is no more have you thought of returning to Chiefofsinners?

DeleteI confess that I miss the Cranmerites, even the ones I disagreed with strongly. Please let us not forget that Martin and others argued like gentlemen, in my experience at any rate, which is how it should be.

DeleteYou are right in the main, so in the spirit of the season I've deleted.

DeleteDamning your fellow Christians to hell is an interesting definition of 'gentleman'...

Delete@ Lain

DeleteLet it go .... erase it from your memory.

@ Gadjo

DeleteAnd Len ... who disappeared so suddenly. I grew very fond of him over the years.

@Lain

DeleteIt seems to me that Christians have been damning their fellow Christians to hell for an awful long time now. And Oscar Wilde in Dorian Gray, I seem to remember, gave us a rather subtle yet pungent take on the concept of 'gentleman'.

@Jack

Len! I seem to remember a dingdong between the two of you about transubstantiation, but I think you both recovered. I personally remember jmarden (not sure I got the name 100% correct) with affection - the lad was upfront about his beliefs and his purpose on Cranmer of converting us to them.

'Tis indeed the season of good will, mistletoe and wine.

Merry Christmas everyone

ReplyDeleteThe Christmas Day special on the Spectator website is the work of a certain Adrian Hilton. Unfortunately, though, it's behind the usual paywall.

ReplyDeletehttps://www.spectator.co.uk/article/in-praise-of-the-church-of-england/

Seems to be freely available.

DeleteNot where I am! I can see only the first few lines, not quite the whole of the first paragraph.

Delete@ Rays

DeleteJack has reproduced the text of this below.

Some carols from Mull Monastery.

ReplyDelete@ Ray - it's too long, but here goes Part I:

ReplyDeleteThe Church of England, like all churches, has always struggled with the tension between the affirmation or assimilation of culture, and the call of the gospel to confront and transform it. Its raison d’etre – its social vocation – is to mediate between the extremes. This was originally between Wittenberg and Zurich (not Wittenberg and Rome, as some believe, though it may have come to be seen as that during the 17th century as anti-Catholicism in the state was incrementally dealt with by statute, and religious liberty increased). But now the CofE’s mediating role is between scepticism and faith, between belief and doubt, pomp and satire, a longing for the sacred combined with a sense that we create the sacred for ourselves.

It does this with an unmistakable Anglican dignity, which is almost a ritualistic disposition embodying the spirit of England. Not only in the beauty and majesty of the Authorised Version, Cranmer’s Prayer Book and echoes of the XXXIX Articles, which together consecrate the ordinariness of English life. It also does so through England’s poets, painters and composers, with which and to which we still baptise our babies, join men and women in holy matrimony, and bury the dead to a solemn peal of bells. We know it through Trollope’s Barchester and Larkin’s ‘Church Going’; through the sonnets of John Donne, the hymns of Herbert and Vaughan, and the verse of TS Eliot, Ruskin and Rosetti. It is a literary and artistic holiness which permeates the heart of England, for churchgoers who fleetingly feel the presence of God in their lives, and who, as Roger Scruton expressed it, ‘wish to be on the right side of Him with the minimum of effort.’

What we see now is a remnant of faith: chocolate-box parish churches where God lurks among polished candlesticks, marble memorials, wooden pews, and the playing of the merry organ, sweet singing in the choir. He reverberates in all His glory through the holy words of biblical English which inspire the holy thoughts of a realm beyond time and space.

And Part II

ReplyDeletePeople of all religions and none still flock to these places because they are sacred: the sacramental character of our national church has survived from the time when the foundations of these shrines were laid, through the storms of iconoclasm and puritanical vandalism, to the world today which is largely forgetting – or has largely forgotten – what goes on inside and what they are for. Again, Scruton expressed it well:

‘English churches tell of a people who for several centuries have preferred seriousness to doctrine, and routine to enthusiasm — people who hope for immortality but do not really expect it, except as a piece of English earth.’

Jesus said: ‘He that is not with me is against me; and he that gathereth not with me scattereth abroad.’ The Church of England says: ‘He/She that is not for me is welcome to be completely indifferent to me; and he/she that that doesn’t want to work with me can just phone when you need a christening, a wedding, a funeral, or a that bit of the Christmas you knew as a child.’

And that Christmas element is interesting: it now hangs with Remembrance Sunday and Royal weddings as a kind of secular religion. Formal state moments – funerals, coronations – are rare, but what the Church of England does annually at Christmas, in the parishes and on the BBC, is an element of civil society. People of all faiths and none find this deeply unifying, spiritually cohesive and relationally meaningful.

Even Richard Dawkins celebrates it: ‘I am perfectly happy on Christmas day to say Merry Christmas to everybody,’ he said. ‘I might sing Christmas carols – once I was privileged to be invited to Kings College, Cambridge, for their Christmas carols and loved it.’

Dawkins is actually not an atheist, even though he is known as the world’s most famous one. I was present at an evening in the Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford a decade ago when he described himself as an agnostic. The Church of England would welcome him with open arms. He appreciates that it satisfies a yearning for national religious ritual to purge us of our transgressions; our inheritance of guilt and resentment. The spiritual philosophy is the seeking of common ground – reifying the parable of the Good Samaritan – humanitarian compassion; healing, reconciling, coexisting in peace and harmony above the political fray.

In those rare moments of state, it falls to the Church of England to facilitate transition. Rather like a person passes through rites of passage – birth, coming of age, marriage, death – the Church of England comforts the anxious as we move from peace to war, from queen to king, from health to sickness. Justin Welby, though, got that one badly wrong during the Covid lockdown, when, for the first time since the 14th century, England’s parish church were locked to those seeking solace and transcendental meaning. It has a uniquely pastoral role to the nation. For Richard Hooker, the architect of the reformed traditions of the English Church and what we now call ‘Anglicanism’, church and society were one.

And Part III

ReplyDeleteThe King was acutely involved in leading men to salvation: ‘A gross error it is, to think that regal power ought to serve for the good of the body, and not of the soul,’ he wrote, ‘for men’s temporal peace, and not for their eternal safety.’

If the state were concerned solely with the material, it would cease to be concerned with people’s welfare in respect of a right relationship with God. Hooker’s articulation of the prerogative of the Crown over its subjects’ religious welfare is the same as that which underlies the role of the Monarch in relation to the Church of England today.

In a speech in 2012, the late Queen articulated her essential Christian mission:

‘Here at Lambeth Palace we should remind ourselves of the significant position of the Church of England in our nation’s life. The concept of our established Church is occasionally misunderstood and, I believe, commonly under-appreciated. Its role is not to defend Anglicanism to the exclusion of other religions. Instead, the Church has a duty to protect the free practice of all faiths in this country.

‘It certainly provides an identity and spiritual dimension for its own many adherents. But also, gently and assuredly, the Church of England has created an environment for other faith communities and indeed people of no faith to live freely. Woven into the fabric of this country, the Church has helped to build a better society – more and more in active co-operation for the common good with those of other faiths.’

The Established Church has a missionary vocation to serve its parishioners – of all faiths and none. It doesn’t seek to exclude or to be out of sympathy with any group of people, because it has an acute pastoral concern for the spiritual wellbeing of all. The fact that its Supreme Governor is also the Head of State means that he is obliged to exercise his public ‘outward government’ in a manner which accords with the private welfare of his subjects – of whatever creed, ethnicity, sexuality or political philosophy.

The Royal Supremacy in regard to the Church of England is essentially a perpetual act of divine worship and service; the right of the Crown in its supervision and administration to provide for the religious welfare of its subjects. While theologians and politicians may argue over the manner of this ‘religious welfare’ or the precise meaning of what Hooker intended by the ‘true fulfilment’ of a ‘right relationship with God’, the focus on such issues serves to alienate and distance the Church of England from many of its parishioners. This hinders its mission in the complex context of pluralism, liberalism and secularity.

Still too long! (gasp) Part IV:

ReplyDeleteThe King was acutely involved in leading men to salvation: ‘A gross error it is, to think that regal power ought to serve for the good of the body, and not of the soul,’ he wrote, ‘for men’s temporal peace, and not for their eternal safety.’

If the state were concerned solely with the material, it would cease to be concerned with people’s welfare in respect of a right relationship with God. Hooker’s articulation of the prerogative of the Crown over its subjects’ religious welfare is the same as that which underlies the role of the Monarch in relation to the Church of England today.

In a speech in 2012, the late Queen articulated her essential Christian mission:

‘Here at Lambeth Palace we should remind ourselves of the significant position of the Church of England in our nation’s life. The concept of our established Church is occasionally misunderstood and, I believe, commonly under-appreciated. Its role is not to defend Anglicanism to the exclusion of other religions. Instead, the Church has a duty to protect the free practice of all faiths in this country.

‘It certainly provides an identity and spiritual dimension for its own many adherents. But also, gently and assuredly, the Church of England has created an environment for other faith communities and indeed people of no faith to live freely. Woven into the fabric of this country, the Church has helped to build a better society – more and more in active co-operation for the common good with those of other faiths.’

The Established Church has a missionary vocation to serve its parishioners – of all faiths and none. It doesn’t seek to exclude or to be out of sympathy with any group of people, because it has an acute pastoral concern for the spiritual wellbeing of all. The fact that its Supreme Governor is also the Head of State means that he is obliged to exercise his public ‘outward government’ in a manner which accords with the private welfare of his subjects – of whatever creed, ethnicity, sexuality or political philosophy.

Fingers' crossed, Part V

ReplyDeleteThe King was acutely involved in leading men to salvation: ‘A gross error it is, to think that regal power ought to serve for the good of the body, and not of the soul,’ he wrote, ‘for men’s temporal peace, and not for their eternal safety.’

If the state were concerned solely with the material, it would cease to be concerned with people’s welfare in respect of a right relationship with God. Hooker’s articulation of the prerogative of the Crown over its subjects’ religious welfare is the same as that which underlies the role of the Monarch in relation to the Church of England today.

In a speech in 2012, the late Queen articulated her essential Christian mission:

‘Here at Lambeth Palace we should remind ourselves of the significant position of the Church of England in our nation’s life. The concept of our established Church is occasionally misunderstood and, I believe, commonly under-appreciated. Its role is not to defend Anglicanism to the exclusion of other religions. Instead, the Church has a duty to protect the free practice of all faiths in this country.

‘It certainly provides an identity and spiritual dimension for its own many adherents. But also, gently and assuredly, the Church of England has created an environment for other faith communities and indeed people of no faith to live freely. Woven into the fabric of this country, the Church has helped to build a better society – more and more in active co-operation for the common good with those of other faiths.’

The Established Church has a missionary vocation to serve its parishioners – of all faiths and none. It doesn’t seek to exclude or to be out of sympathy with any group of people, because it has an acute pastoral concern for the spiritual wellbeing of all. The fact that its Supreme Governor is also the Head of State means that he is obliged to exercise his public ‘outward government’ in a manner which accords with the private welfare of his subjects – of whatever creed, ethnicity, sexuality or political philosophy.

The Royal Supremacy in regard to the Church of England is essentially a perpetual act of divine worship and service; the right of the Crown in its supervision and administration to provide for the religious welfare of its subjects. While theologians and politicians may argue over the manner of this ‘religious welfare’ or the precise meaning of what Hooker intended by the ‘true fulfilment’ of a ‘right relationship with God’, the focus on such issues serves to alienate and distance the Church of England from many of its parishioners. This hinders its mission in the complex context of pluralism, liberalism and secularity.

Jack has had enough of this now! Part V:

ReplyDeleteThe King was acutely involved in leading men to salvation: ‘A gross error it is, to think that regal power ought to serve for the good of the body, and not of the soul,’ he wrote, ‘for men’s temporal peace, and not for their eternal safety.’

If the state were concerned solely with the material, it would cease to be concerned with people’s welfare in respect of a right relationship with God. Hooker’s articulation of the prerogative of the Crown over its subjects’ religious welfare is the same as that which underlies the role of the Monarch in relation to the Church of England today.

In a speech in 2012, the late Queen articulated her essential Christian mission:

‘Here at Lambeth Palace we should remind ourselves of the significant position of the Church of England in our nation’s life. The concept of our established Church is occasionally misunderstood and, I believe, commonly under-appreciated. Its role is not to defend Anglicanism to the exclusion of other religions. Instead, the Church has a duty to protect the free practice of all faiths in this country.

‘It certainly provides an identity and spiritual dimension for its own many adherents. But also, gently and assuredly, the Church of England has created an environment for other faith communities and indeed people of no faith to live freely. Woven into the fabric of this country, the Church has helped to build a better society – more and more in active co-operation for the common good with those of other faiths.’

The Established Church has a missionary vocation to serve its parishioners – of all faiths and none. It doesn’t seek to exclude or to be out of sympathy with any group of people, because it has an acute pastoral concern for the spiritual wellbeing of all. The fact that its Supreme Governor is also the Head of State means that he is obliged to exercise his public ‘outward government’ in a manner which accords with the private welfare of his subjects – of whatever creed, ethnicity, sexuality or political philosophy.

The Royal Supremacy in regard to the Church of England is essentially a perpetual act of divine worship and service; the right of the Crown in its supervision and administration to provide for the religious welfare of its subjects. While theologians and politicians may argue over the manner of this ‘religious welfare’ or the precise meaning of what Hooker intended by the ‘true fulfilment’ of a ‘right relationship with God’, the focus on such issues serves to alienate and distance the Church of England from many of its parishioners. This hinders its mission in the complex context of pluralism, liberalism and secularity.

A principal tension is that we now have bishops who swear to uphold the sacred doctrine handed down to them, who then issue pamphlets and publish books which ditch Cranmer and Hooker in favour of Durkheim and Weber. They take the sociology of religion more seriously than doctrinal integrity and historical tradition, believing – in a BBC Radio ‘Thought for the Day’ kind of way – their Anglican sociology to be more in tune or more relevant to the national life. Yet they are seemingly oblivious to the spiritual yearning in moments of crisis, and the longing for meaning in human life. They boast and broadcast the virtues of food banks in churches, as though the feeding of the 5,000 were a model for the postmodern Christian mission; living by tomato soup, tinned meats and packets of pasta alone has supplanted ‘every word that proceedeth out of the mouth of God’. It is a laudable mission of welfare, but one that is almost oblivious to the reason people were originally seeking out Jesus, which was not for a bread and fish takeaway.

On the floor - (why of why did he do this) Part whatever:

ReplyDeleteAn important dimension of the Church of England’s core mission is the reification of the search for purity and purification in the nation – if that isn’t a metaphysical contradiction. We sin individually, and we trespass and transgress nationally. And somehow the faithful CofE helps us to purge the evils and inherited guilt of the past and create in us a clean heart, a new beginning, spiritual renewal and social peace. Its rituals may be imperfect and provisional, but it helps the whole nation, as Scruton said, ‘for a moment to stand in the light of eternity, from which we can return duly cleansed into the here and now.’

nd, for all its faults, the Church of England communicates or radiates a sacred beauty, or a beautiful sanctity. We see it in everything from parish prayers, stained glass and hymns to the burial of queens and the coronation of kings. It is perpetually mediating between God and man, between Roman and Anglican Catholicism, between high and low, between American liberal and African conservative, between biblical doctrine and biblical scholarship, between secularity and spirituality, contemporary ‘relevance’ and historic patristic faithfulness, maintaining the spiritual order in the life of the individual and in the community. It provides the Eucharistic moments in the life of our nation, inculcating a common moral code – ‘British values’, if you will – with sacramental authenticity and an almost apostolic authority.

The Anglican Settlement is one of patriotic loyalty, natural morality, dignity and compromise; of a shared sense of belonging and self-understanding. It keeps the finitude of our humanity in parliamentary perspective: we are not gods, we are not immortal. There is something for us after death, and our life should be about loving and forgiving and seeking ‘the peace of God which passeth all understanding’ in a world in which so much is irrational, unintelligible and evil.

The Church of England aspires to a collaborative Christocentric synthesis in the state, if not a pacifying, postmodern, political-social-spiritual syncretism, and ‘Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall be called the children of God.’

Merry Christmas, one and all.

Thank you, Jack, for all your hard work. And on Christmas Day, too, of all days in the year!

ReplyDeleteNow that I've had time to read it, thank you again, Jack. It's a very thoughtful article, very balanced, very carefully written. It brings out, among other things, what a great pity it is that we have lost His Grace's regular blogposts.

ReplyDeleteIt's only a brief point mentioned in passing, but His Grace makes an illuminating remark about Richard Dawkins, agnosticism, and Christmas.

@ Ray

ReplyDeleteHmmm .... Jack's not so sure. It's more a defence of the cultural Englishness of the Established Church of England and it's incorporation of incompatible theologies, (including now, it seems, secularism) than a reflection on the Christ-child.

Thank you, Jack - I fear you are correct. Cranny's "Anglicanism" is about cultural liberalism with a religious tinge.

DeleteThat's why it has capitulated to the post-Christian mentality in British society and is terrified that a Starmer government would kick bishops out of the House of Lords.

And the gay sub-text runs through the Church of England because they are everywhere in the cathedrals.

The gay, partnered Dean of Canterbury is joined by the same-sex "married" Dean of Chelmsford, and thd gay bishops Welby has appointed to Grantham and Sherborne.

Evangelicals will leave.

@ Brian

DeleteIn one of Jack's unguarded moments, shared with Ardenjm under another profile and so it wasn't deleted when Cranmer nuked his site:

"Funny, isn't it, how you find it so intolerant, unacceptable or 'bigoted' when people question the authority and infallible precepts of the church that calls itself 'Catholic', yet here you are declaring that the Church of England has no valid orders and, therefore, no valid sacraments, which is to say, in your opinion, it is not a church, or any part of the Church catholic. This is an Anglican blog. You may view it as your personal mission field - and you are certainly not obliged to believe what we believe - but, in all fairness, if someone called your church a false church or the Whore of Babylon, or intimated that your pope was the antichrist and the Mass an outrageous blasphemy, you'd doubtless find it quite offensive. The Church of England is Catholic and Reformed: it is a valid church and part of the Church catholic. Please get over it."

This was during a somewhat heated exchange over Hilton receiving the Eucharist without permission during a visit to Rome.

Of course, Jack was tempted to ask "Which 'Church of England' would that be? The evangelical; the Anglo-Catholic; or the liberal "ecclesiastical community?" But, having been banned twice, he didn't want to risk a third expulsion.

@Jack

DeleteI have never really understand how CofE doctrine operates, not having been raised in the church. The 'via media' thing is genuinely interesting from a late medieval standpoint but I wonder if it contains the seeds of it's own destruction if it can't ever quite nail its colours to a mast.

@ Gadjo

DeleteIt has always been a church of political and theological compromise, united only by national ambition and rejection of the secular and temporal authority of the Pope and Bishops - not forgetting the wealth of the Church at the time!.

This is a good overview by an ex-Anglican cleric who converted to Catholicism of the situation today. And it's getting worse.:

"I attended an Anglican seminary of the Evangelical persuasion called Wycliffe Hall, and down the road was the Anglo-Catholic seminary called St. Stephen’s House. The two were totally opposed in theology, liturgical practice, culture, and ethos. In Oxford was an Anglican seminary which was “broad church,” or liberal. This third strand of Anglicanism has always been a kind of worldly, established, urbane type of religion that is at home with the powers that be and always adapts to the culture in which it finds itself.

"These three forces co-exist in the Anglican church—united by nothing more than a shared baptism, a patriotic allegiance to the national church, and the need to tolerate each other. Unfortunately, the toleration frequently wears thin. The Anglo-Catholics, the Evangelicals, and the liberals are constantly at war. Their theology, their liturgy, their politics, and their spirituality are in basic contradiction to one another.

"Other influences have complicated things further, and the three main strands of Anglicanism have divided into sub-strands depending on the influences of various individuals and movements. Just about every permutation and mixture of politics and religion is found within the Anglican church."

(Fr Dwight Longeneker)

@ Gadjo

DeleteMeant to add, they also have two competing sources of 'doctrine'. The 39 Articles and the Book of Common Prayer.

As a Prod I am not especially concerned about the fracturing of denominations as long as they still adhere to core Christian principles; but siding with secularism and other -isms, which seems to be where the CofE is these days, kinda counts them out. I am curious to see whether breakaway forms of Anglicanism and e.g. African bishops can keep the thing going without Cantebury, but I have my doubts.

DeleteThank you for this, Jack. I can't help but think it's rather rose tinted.

ReplyDeleteWhen you realise that there is a very strong component of the Church of England that is essentially a professional classes guild, much of what Hilton writes makes sense. What is deified is a particular set of social relationships - not necessarily in practice, but in theory, and as anyone who has spent any amount of time around the professional classes will know, there is nothing like theory to justify the existence of an institution.

DeleteYes, that's exactly it. Very well put. I didn't recognise any of my own experience of the CofE in deprived and rural areas in that piece. It's much more the point of view of the dreaming spires and ivory towers.

DeleteA blessed Christmas to you.

Yes, choirs, independent schools, cathedral canons, musicians and a bureaucracy created by General Synod - this is what Hingon is really talking about.

DeleteThe Heritage Industry tied into the Monarchy.

Not exactly the Gospel.

@ Brian

DeleteIt's at the heart of Hiltons alter-ego and his oft times crabiness. Jack was once tempted to call him Archbishop Crabner - but resisted.

He's conflicted.

Hilton can be brilliant and incisive when the differences between Christianity and the world are clear and need stating, but there are times when his conservative liberalism (not to be confused with liberal conservatism) leads him to affirm people or positions that are not really or consistently Christian. Martin Sewell was given anple acreage to make the case for Maryn Percy, no friend of evangelicals or catholics: and much earlier, Hilton wrote eloquent commendations of Big Brother contestant Jane Goody as she was dying of cancer; and the thin faith of David Cameron, the architect of "same-sex marriage" (for Cameron, the proudest achievement of his premiership, rather than Brexit).

DeleteAnglican scholar Gerald Bray was fond of saying that the British people look on the Church of England as the piblic looks on their public libraries: places to be visited as and when you wish but with no expectation of commitment.

Of course, the libraries were closed as well as the churches during the pandemic, and most of us don't find them of much interest today.

@ Brian

DeleteJack thought his article on Jane Goody was okay - way too 'sugary' and emotive; but the sentiment was correct and Christian.

The other aspect of his perspective Jack found extremely irritating was his thinly concealed anti-Catholicism. As if the Common Market had all been a secret papal plot to impose Catholic social doctrine on Great Britain.

I wish that Melvin Tinker were still with us to give a working man's positive take on Anglicanism.

DeleteMerry Christmas all!

ReplyDelete